Alain Delon and the Beauty of Evil

A few months ago, I went to a screening of Jean-Pierre Melville’s classic Le Samuraï (1967), starring a young Alain Delon. No one could have known at the time of the screening that Delon would pass away just a few weeks later on the 18th of August at the age of 88. Since then, I have watched several of his films, and collectively they trouble my soul with many questions about the relationship between evil and beauty. It’s beginning to disturb my Platonic sleep.

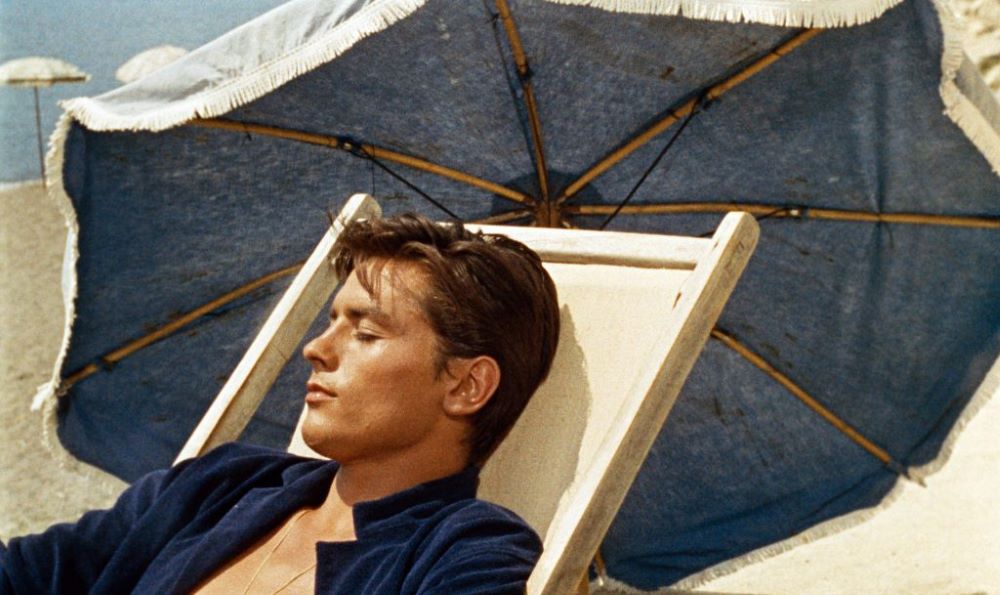

Delon is consistently described by the critics as “beautiful” rather than “handsome,” and this is just the right word, although you would be quite mistaken if you thought this suggested anything soft or effeminate. His is a dangerous, crystalline beauty that attracts at the very moment that it resists approach. His famous blue eyes suggest something of the predatory animal, a panther or a bird of prey: steady, intelligent, cold, at times regal, always lethal.

In many of his roles, Delon’s deadly beauty is cast to good effect. In his breakout role, for example, he starred in Plein Soleil (1960), the French adaptation of Patricia Highsmith’s novel The Talented Mr. Ripley. Delon’s character, Tom Ripley plays a pathological liar who has conned his way into the society of the wealthy and handsome Dickie Greenleaf (called Philippe in the French version) as Greenleaf idles around in Italy. The conniving and envious Ripley, early in the film, sneaks on Greenleaf’s fine clothes, using his hairbrush, and whispering the things Greenleaf says to his fiancée, Marge, all while admiring himself in the mirror. Eventually, while they are out sailing on the utopian waters of the Mediterranean, Ripley kills Greenleaf and assumes his identity, even using his typewriter and signature to withdraw enormous sums from his bank account.

I prefer the French title Plein Soleil to the usual translation Purple Noon because it communicates the way that a strong Mediterranean sun saturates every scene of the film even—perhaps especially—when Ripley dumps the body of a man he has just killed over a wall in the dead of night. Throughout the film, one never forgets the full, cloudless sun shining straight down on a white yacht sailing over blue waters, while rich, beautiful people lounge and tan, argue and murder on its deck. Like Oedipus the King, Apollo is an offstage character in the drama.

In Le Samuraï, Delon plays a careful, punctilious assassin named Jef Costello, who puts on white gloves before shooting his victims. The film opens with a long, wordless sequence in which we watch him wake up in an austere Paris apartment, don a trench coat, steal a classy car, set up a complex alibi, walk into a moody jazz lounge, slip into a back office, put on his white gloves, and at point blank, execute his target.

The photography, directed by the true artist Henri Decaë, maintains a consistent palette of cool, high-contrast blues, grays, blacks, and whites creating a color version of the film noir aesthetic. It conveys the sterile elegance of the quiet killer, as though Delon’s blue eyes, dark hair, and impossibly immaculate pale face imposed themselves by the sheer force of their perfection on the colors of the whole world.

Writing about Delon and the photography of Decaë, Sarah Imogen Smith remarks “how easily moral compasses can be deranged by the magnetism of beauty.”1 In many noir films, she observes that we are drawn to cool killers. It’s more complicated than realizing that a bad man might have a pretty face. The whole aesthetic of such films, the particular brand of “cool” that they display, has everything to do with the badness of the characters. Sometimes the characters do have redeeming qualities, but we wouldn’t be attracted to them in the same way if they weren’t bad to begin with.

In Monsieur Klein (1976), a slightly older Delon plays a wealthy art dealer, the titular Robert Klein, in the middle of German-occupied Paris. Early in the film, we find this man in a silk bathrobe lounging at home in an apartment packed with opulent aesthetic objects: bronze sculptures on every table, rare paintings in front of tapestry-covered walls. The dramatic action starts when Klein buys an Old Dutch Master painting for far less than it is worth from a Jewish man who is desperate to raise what money he can in order to flee France. Again, beauty is mixed with evil, and not mixed in an accidental way, but mixed in such a way that beauty is directly implicated in Monsieur Klein’s crime.

These films touch a deep anxiety about beauty because, if they speak the whole truth, they threaten the alliance between the Beautiful and the Good. It is sometimes said that Baudelaire was the first great artist to champion the aesthetics of evil and that his Les Fleurs du mal are meant to show us little vignettes of depravity that are supposed to be beautiful not in spite of the depravity but because of it. To a Platonist like me, who believes that the beautiful in its very essence is the manifestation of the good, such an idea is not just scandalous or shocking—it’s metaphysically impossible.

Perhaps the anxiety runs deeper, however. Perhaps it’s not just possible for some particular evil things to be beautiful in their evil. Perhaps, more shocking still, all beautiful things are evil in their beauty. Perhaps the beautiful itself is something corrupt, an alluring counterfeit of the good, always dressed up like Lady Macbeth in royal finery but rubbing and rubbing bloody hands that will never be clean.

Not so subtly in the background behind this line of thinking is an association between beauty and wealth. Money acts as a middle term between beauty and evil so that beautiful equals rich and rich equals evil. In Plein Soleil, the yacht, the fine clothes, the lavish hotel rooms all drive Tom Ripley’s covetous pathology. In Monsieur Klein, the aesthete’s apartment comes from a covenant with Mammon. In Le Samuraï, although the bare apartment stands in stark contrast to that of Monsieur Klein, the whole plot revolves around a large sum that a cabal of mysterious elite is paying to have somebody killed.

Such a linkage between beauty, wealth, and evil is especially appealing to those who view the world primarily in terms of class struggle. The rich guys are the bad guys and they have nice things. The poor guys are the good guys who have ugly things. Hence we have the spectacle of middle-class kids who want to look like revolutionaries intentionally tearing up their clothes and disfiguring their hair. The irony, of course, is that the rich are thought to be evil primarily because they keep the nice things for themselves rather than sharing them with the poor, who actually do want these things and hence, by their own logic and desires, affirm the goodness of material beauty.

The condemnation of beauty is much worse when it goes from this-worldly politics to other-worldly religion. A certain type of dour-face ascetic spirituality has always been found in the heretical sects of most faiths. It seems to be one of a few basic configurations of attitude that show up again and again in totally different traditions, and its adherents tend to have a recognizable personality type. Although it’s impossible to say, I wonder whether people of such a personality tend to adopt this kind of religion or whether the adoption of such a religion tends to distort people’s personality into the type. I suspect it’s a bit of both, but either way, these people end up pretty sad.

According to the dour-faced religion, beautiful things are always suspicious. Beautiful possessions, like those of Monsieur Klein, are the sign of ill-gotten gains. A beautiful face, like that of Tom Ripley, is the sign of a frozen heart. Inverting the same logic, the Good must always be ugly. If something is hard and unpleasant, it must be good precisely because it does not attract our worldly desires. The more ugly something is, the better it must be.

Such a view leans heavily on the contrast between seeming and being. We all know that appearances can be deceptive and that Delon’s pretty face and winsome smile might conceal murderous intent. But the dour-face folks take the appearance of something as conclusive evidence that the substantial core underneath must be rotten. Beautiful appearances—just because they are beautiful—are always evil, and therefore a good core must always come with an ugly appearance.

In defense against all these accusers of beauty, I call to witness one of my heroes, Hans Urs von Balthasar:

We no longer dare to believe in beauty and we make of it a mere appearance in order the more easily to dispose of it. Our situation today shows that beauty demands for itself at least as much courage and decision as do truth and goodness, and she will not allow herself to be separated and be banned from her two sisters without taking them along with herself in an act of mysterious vengeance.

What vengeance will beauty exact if we turn our backs on her as an enemy of the good?

We can be sure that whoever sneers at [Beauty’s] name as if she were the ornament of a bourgeois past—whether he admits it or not—can no longer pray and soon will no longer be able to love.2

The cheap way to rescue ourselves and restore the alliance between the beautiful and the good would simply be to deny the beauty of Delon, his films, and the characters he plays. We might say that such things are “merely pretty” and that “true” beauty lies elsewhere. But such a move would betray the very foundations of our relationship to beauty. It would deny the manifest evidence of our experience—it’s just a fact that the films are full of beauty—and the very essence of beauty lies in its manifestation. To deny the manifestly beautiful and pretend instead that some secret, invisible beauty is the true beauty amounts to denying the reality of beauty altogether.

Instead, I think we must take a more difficult path. We must acknowledge the beauty of evil things but guard against—at the risk of our souls—Baudelaire’s error that evil things are beautiful because they are evil. Instead, evil things may be beautiful in spite of their evil, and insofar as they are beautiful, the beauty itself is good. In simple cases, the two are related accidentally. A murderer has lovely blue eyes. So what? The eyes by themselves are beautiful and this is good. The man is a murder and this is evil. The two facts are unrelated except that they happen to be facts about the same man. In the more complex cases like those of Delon’s films, however, we must say more.

Here, the situation is more like that of a clever lie. The lies that work, of course, are those that contain some truth. The more truth they contain and the more closely intertwined the lie is with the truthful core, the more effective the lie becomes. Recognizing that something is a lie, we would be gravely mistaken if we rejected wholesale the truth it contained or even downplayed the truthfulness of the truth because it was bound up cleverly in a lie. This remains so even when we have difficulty untangling the threads of the lie from the threads of the truth. Similarly, I think we must acknowledge that there really is something fine about the objects in Monsieur Klein’s apartment even though they were purchased with blood money and in the context are collectively a symbol of decadence. We must acknowledge that there really is a compelling power in the disciplined lethality of Costello even if that lethality is deployed in the service of an evil cabal.

We must be careful, however, because, even though beauty manifests itself, our capacity to judge beauty is not infallible, much less our capacity to sort out good from evil in complex cases. So perhaps it’s good that our sleep should be troubled, at least a little.