The Socrates Effect

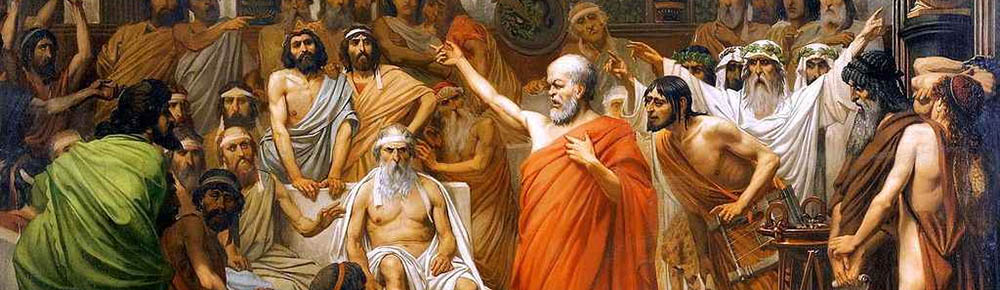

A curious thing happens when a young man meets Socrates for the first time. In the streets of Athens, he would wrangle public figures all covered in the dust of the marketplace under the pitiless midday Mediterranean sun. They say he was ugly, with a snub nose and repulsive features. But he had a way with words. So good, in fact, that many mistook him for a rhetorician or a sophist. Was this some kind of stunt? A way to advertise his services as a trainer in public speaking? His technique certainly suggested a road to power because day after day he showed that he could best the most prominent men in Athens by trapping them in their own words.

In contemporary education circles, one often hears about the virtues of the “Socratic Method.” What is meant, however, often amounts to little more than “teaching by asking questions.” When they get really advanced they mean, “teaching by asking leading questions.” Socrates himself, however, didn’t exactly teach, and his questions, one after another, drove at a focused goal: public humiliation. This is an underappreciated boon to the life of the mind, but I doubt very much whether our educators want it in their classrooms.

The questions of Socrates systematically expose a certain baffling inability in those who claimed to know. Ostensibly, an expert in any subject ought to be able to “give the logos.” On the one hand, this phrase can mean “give the definition of some term.” What is the definition of “courage” (Laches) or “holiness” (Euthyphro)? On the other hand, this phrase can also mean “give an account of yourself” in a court of law. Where were you on the night of the murder? Can you explain where the money has gone?1 The leading men of Athens can do neither. Their inability to say exactly what they mean or make obviously true statements square with one another means that they cannot justify their own existence as experts and competent leaders.

To a young man, the humiliation of successful men in the previous generation holds a perennial fascination. They gathered around. They enjoyed the spectacle. They imitated the method. A few of them listened and understood.

They saw that the questions were not a stunt, not an advertisement. They were sincere. They saw that these questions might just as well be put to them and that they too would face the humiliation of stammering self-contradiction. And most important of all, they came to believe that such an inability to give the logos really ought to be humiliating, not just before the crowds but before themselves. What am I doing with my life if I cannot give straight answers to simple questions about friendship, courage, beauty, or death?

Once this encounter with Socrates has taken place, a deep alteration occurs in the soul of the young man. He begins to internalize the voice of Socrates. He begins to ask himself, in the privacy of his own mind, those same kinds of questions. Before long, the habit of doing so becomes an inner compulsion that he cannot quit even if he wanted to. Long after his death, the gadfly of Athens continues on as the inner gadfly of the mind.

The mind stung by this gadfly becomes perplexed, especially at its own perplexity. Then it begins to theorize. It begins to formulate better answers to the Socratic voice inside the head, but that voice asks further questions of those answers. Eventually, the mind grows from the imbecility of Euthyphro-type answers into the cleverness of Cebes-type answers, answers that begin to challenge and impress Socrates. Even so, the more sophisticated and articulate answers enable more sophisticated and articulate questions, until whole systems of philosophy are knit together proposition by proposition.

Many young men in that generation underwent this change, and the effect upon the culture of Athens in the years immediately following the death of Socrates in 399 was profound. One young man among them, however, was perhaps more nettled by the gadfly than the others. What he did about it was certainly more consequential. The dialogues of Plato have immortalized the spirit if not the very words of Socratic interrogation, and as a result, generation after generation of young men have similarly encountered Socrates and experienced the alteration that the encounter causes in their souls.

As an undergraduate philosophy student at the University of Kentucky, I remember sitting at a campus café with two friends. One was a dismissive materialist who began to mock the ancient texts that we were, in his view, uselessly forced to read. I will never forget the vehemence with which my other friend responded, “No. You are wrong. Socrates is alive. Last night while reading the Phaedo, at that moment when Socrates looks down and tousles young Phaedo’s hair, warning him about the dangers of coming to hate the logos, Socrates was speaking to me. I knew in my bones that I—in the present—was being addressed, that I was being warned.”

As a professor at Georgetown College, a freshman student came into my office. He had been assigned a reading from the Apology by an English professor, and that night he had been haunted. He came, obsessed, to the office hours of that English professor, and she had sent him to me. He is now a graduate student in philosophy.

I suspect that this is the psychological origin of Western philosophy, but I’m not all sure that it has been an unalloyed good. Surely the inner hunger to seek the truth has been a good thing. Surely the sincere preference for being over seeming has been a good thing. Surely the loss of confidence in one’s own wisdom and the resulting epistemic humility have been good things. But I sometimes wonder whether the endless demand to give the logos is more than the human mind can bear.

Cf. the use of this phrase in the parable of the dishonest manager in Luke 16:2.↩︎